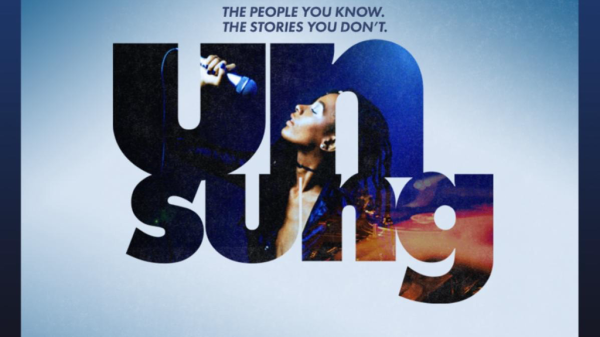

Years before she was known for classic R&B tunes like “Young Hearts Run Free,” “You Got the Love,” and “Nights on Broadway”; the GRAMMY® Award nominated soul singer Candi Staton literally had a driver’s seat view to civil rights history. She was a 24-year-old mom of two toddlers on September 15, 1963, when members of the Klu Klux Klan blew up the historic 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, AL with 19 sticks of dynamite. The explosion killed four young girls, injured two dozen others, and ignited an angry backlash that was felt around the globe. Listen Link: https://li.sten.to/1963

Years before she was known for classic R&B tunes like “Young Hearts Run Free,” “You Got the Love,” and “Nights on Broadway”; the GRAMMY® Award nominated soul singer Candi Staton literally had a driver’s seat view to civil rights history. She was a 24-year-old mom of two toddlers on September 15, 1963, when members of the Klu Klux Klan blew up the historic 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, AL with 19 sticks of dynamite. The explosion killed four young girls, injured two dozen others, and ignited an angry backlash that was felt around the globe. Listen Link: https://li.sten.to/1963

“I know I speak on behalf of all Americans in expressing a deep sense of outrage and grief over the killing of the children yesterday in Birmingham, Alabama,” President John F. Kennedy said in a White House statement the following day. “It is regrettable that public disparagement of law and order has encouraged violence which has fallen on the innocent. If these cruel and tragic events can only awaken that city and State–if they can only awaken this entire Nation–to a realization of the folly of racial injustice and hatred and violence, then it is not too late for all concerned to unite in steps toward peaceful progress before more lives are lost.”

Staton saw the madness and mayhem first-hand. The 83-year-old singer has recorded a coffeehouse-styled soul soliloquy, “1963” (Beracah Records), to commemorate the 60th anniversary of that day and to draw a parallel to today’s issues. “I never experienced anything like that before,” she says. “We had gone to a little church a few blocks away from the 16th Street Baptist Church. The choir had sung and suddenly, somebody burst through the front door and started screaming that 16th Street Church was bombed and people were rioting. So, he told everybody to rush home to get safety. Black people were turning over the cars of every white person they saw. White people and black people were throwing things at each other in the streets. Police were shooting guns into the air to scare people. It was just one of the worst days ever.”

Staton grew up in rural Hanceville, Alabama, about 40 minutes outside of Birmingham where Jim Crow segregation was a way of life. As a teenager, she toured the deep south as a member of The Jewell Gospel Trio. “We used to be on the road with Sam Cooke, The Soul Stirrers, Mahalia Jackson, and we traveled in a caravan of cars,” she says. “We did that because the police would stop anybody and harass them. If we were in a caravan, they had witnesses, so they were less likely to do something crazy. I remember one night; the police made the Fairfield Four quartet get out of the car and start singing. The police said that if they don’t sound good, they would shoot them. So, while they were singing, they shot their guns at the ground near their feet. We had to stay at boarding houses because no hotels would welcome us. We had to get food at the side door of a restaurant. It was so dehumanizing.”

The Jewel Trio opened for actor-activist Paul Robeson during some of his political concerts and the group used to play in the yard of civil rights leader, Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune. “She used to make us bologna sandwiches,” Staton recalls. It’s against this tableau that she decided to make a song about that day. “I rarely hear anyone call out the names of those girls,” Staton says. “I wanted to call their names like people call George Floyd’s name. I also didn’t want to act like this was just a thing of the past. These kinds of tragedies are still happening. All the school shootings we’ve seen in recent years, reminded me that what happened in 1963 is still happening in 2023.”

A seasoned group of musicians provided the backdrop. Staton’s eldest sons, Marcel, and Marcus Williams, who were with her that Sunday in 1963, laid the music. Marcel played bass and Marcus (Isaac Hayes, Peabo Bryson) played drums and produced the track. Myra Walker (Pop Staples, Dionne Warwick) played the keyboards, and Steve “Lfthnd” Lewis, who is known throughout the Atlanta, Georgia Jazz community for his left-handed guitar skills. added some lite guitar. Staton joined her daughter Cassandra Hightower, and Walker on the background vocals. Listeners can hear the emotion in Staton’s voice as she tells the story in the song that she recorded in a single tape. “I could only do that one time,” she says. “I was reliving it and started to cry.”